The Assassination of Julius Caesar: The Ultimate Political Betrayal

Perhaps no event captures the theme of politics and betrayals of Ancient Rome better than the assassination of Julius Caesar. A gifted general and reformer, Caesar’s rise to power sparked fear and resentment among Rome’s senators. After securing victory in the civil war against Pompey, Caesar declared himself dictator for life, a move that alarmed many of his peers who believed he was steering Rome toward tyranny.

On March 15, 44 BCE—the Ides of March—Caesar was betrayed by a group of senators, including his close friend Brutus. Led by Marcus Junius Brutus and Gaius Cassius Longinus, these conspirators saw Caesar’s assassination as a means to restore the Republic. Yet, the murder backfired, plunging Rome into chaos and sparking another civil war. Caesar’s death marked a turning point, symbolizing the extreme lengths Romans would go to protect or seize power.

Political Feuds of the Second Triumvirate: Antony, Octavian, and Lepidus

The Second Triumvirate was formed in the wake of Caesar’s assassination to restore order, but it soon became a stage for more political feuds and betrayals in Ancient Rome. This alliance, made up of Octavian (later Augustus), Mark Antony, and Lepidus, was intended to stabilize Rome and avenge Caesar’s death. However, tensions quickly mounted.

Lepidus was the first to be ousted, pushed into political obscurity by Octavian and Antony. The real power struggle then ignited between Octavian and Antony, who had allied himself with Cleopatra of Egypt. Fearing Antony’s ambition and influence, Octavian launched a propaganda campaign to paint him as a traitor to Rome. This feud reached its climax at the Battle of Actium in 31 BCE, where Octavian’s forces defeated Antony and Cleopatra. Their tragic suicides left Octavian as the unchallenged ruler of Rome, marking the end of the Republic and the rise of the Roman Empire.

The Paranoia of Emperor Tiberius and the Downfall of Sejanus

As Rome’s first emperor, Augustus sought to establish stability, but his successor Tiberius would usher in an era of suspicion and betrayal. Known for his paranoia, Tiberius withdrew to the island of Capri, leaving Rome under the control of his ambitious advisor, Lucius Aelius Sejanus. Sejanus took full advantage of Tiberius’s absence, using his position to execute rivals and consolidate power.

Sejanus’s betrayal was eventually discovered, leading to his arrest and execution in 31 CE. The episode deepened Tiberius’s mistrust, resulting in a reign marked by fear and a relentless purge of perceived enemies. This betrayal underscored the dangers of unchecked power and set the stage for a succession of politically charged intrigues in the Roman Empire.

The Reign of Caligula: A Tyranny of Political Betrayals

The reign of Caligula is another prime example of the political feuds and betrayals of Ancient Rome. Initially hailed as a promising ruler, Caligula’s leadership quickly descended into madness and brutality. His erratic behavior and violent outbursts led to the alienation of the Senate and the Roman elite.

Caligula’s betrayal of his supporters—often executing or humiliating those closest to him—created a climate of resentment and fear. In 41 CE, a conspiracy within his own guard resulted in his assassination. Caligula’s death highlighted the instability of imperial rule and showed that even the most powerful rulers were not immune to betrayal.

Nero’s Reign: Paranoia, Conspiracies, and the Great Fire of Rome

The infamous emperor Nero inherited a turbulent empire rife with political feuds and betrayals. Initially popular, Nero’s descent into paranoia led him to execute his mother, Agrippina the Younger, who had helped him ascend to power. As Nero’s suspicions grew, he ordered the deaths of numerous senators, friends, and even his wife Octavia.

In 64 CE, Rome was ravaged by a great fire, and rumors spread that Nero himself had started it. Although the true cause remains unknown, Nero’s attempt to deflect blame onto Christians added fuel to the fire of public discontent. Eventually, conspirators within the Senate, weary of his tyrannical rule, forced Nero to flee Rome. Cornered and facing execution, he chose to take his own life. Nero’s tragic end underscored the cyclical nature of betrayal that characterized Ancient Rome’s political landscape.

The Legacy of Political Feuds and Betrayal in Ancient Rome

The political feuds and betrayals of Ancient Rome—from Julius Caesar’s assassination to Nero’s self-inflicted demise—paint a portrait of a society marked by ambition, loyalty, and treachery. These episodes reveal how power in Rome was both a prize and a peril, often secured through violence and deception.

While these political feuds ultimately led to the empire’s expansion and consolidation, they also sowed seeds of distrust that contributed to Rome’s eventual decline. The legacies of these betrayals are still studied and marveled at today, providing timeless lessons about the corrupting influence of absolute power and the human cost of ambition.

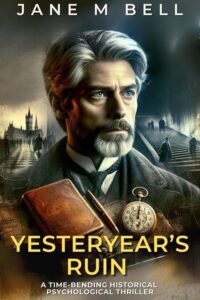

As I wrap up this week’s journey into historical politics on Bell’s Books and Blog, I’d like to thank you for joining me on this adventure! If you enjoyed the read, don’t forget to sign up for my weekly newsletter at books.janembell.com. As a special thank-you, you’ll receive a free digital copy of Yesteryear’s Ruin, the prequel to my latest novel, Yesteryear’s Echo. Just click on the Yesteryear’s Ruin book cover!

For more history and mystery, don’t forget to tune in to this week’s Bell’s Books and Blog Podcast, where you can listen to the rest of the content in this week’s blog.

You can catch the latest podcast episode on my podcast page or find links to your favorite platforms like Amazon Music, Audible, Apple Podcasts, Spotify, and more. Be sure to subscribe wherever you listen, so you don’t miss an episode!

Until next time—stay curious, keep questioning, keep exploring, keep reading and, of course, keep the past alive!

Wishing you a wonderful week!

Warm regards,

Jane M. Bell

“Yesteryear’s Ruin” captures the essence of human resilience in the face of unimaginable loss. Through a narrative that weaves together love, despair, and the quest for redemption, this historical psychological thriller invites readers into a world where the past is not merely a memory, but a realm that may hold the key to our deepest desires and darkest fears.

“Yesteryear’s Ruin” captures the essence of human resilience in the face of unimaginable loss. Through a narrative that weaves together love, despair, and the quest for redemption, this historical psychological thriller invites readers into a world where the past is not merely a memory, but a realm that may hold the key to our deepest desires and darkest fears.